Latinx ACT UP: Queer Chicana/o and Puerto Rican Transnational AIDS Activism

This article is authored by René Esparza, from the 2018-19 cohort of the LGBTQ Research Fellowship program at the One Institute.

On October 21, 1991, ACT UP/LA dispatched a letter to the Mexican Consulate in Los Angeles, voicing concern about the growing influence of what it deemed a “dangerous extremist group,” El Instituto Schiller, in Baja California. That institute was affiliated with Lyndon LaRouche, a right-wing American extremist who in 1986 unsuccessfully mounted a California campaign to quarantine people with AIDS. In Baja California, El Instituto Schiller was similarly pushing for mandatory testing, closed borders, and mass quarantine. In the letter, ACT UP/LA feared that “as travelers and consumers of the neighboring state of Baja California, [we] feel that we are going to be affected by these repressive laws by the simple fact of looking ‘suspicious’.”[1] If those writing the letter worried they would look “suspicious” when visiting Baja California, then it is likely those writing the letter were either not Latinas/os or, at the very least, did not occupy the same socioeconomic status as residents of Baja California—assuming such a class distinction physically underscored their Americanness. Of significance here is that although ACT UP/LA did engage in some transnational work in Mexico, it did not necessarily do so as the “Latina/o members of ACT UP/LA.” This approach differs markedly from that taken by the Latina/o Caucus of ACT UP/NY.

Comprised of primarily queer Puerto Ricans, the Latina/o Caucus centered its efforts not just on Latinas/os in New York but on Latin American communities throughout the Global South, most notably Puerto Rico. Because the high prevalence of HIV among US-born Puerto Ricans was reflected in the high prevalence of HIV among island-born Puerto Ricans, the Latina/o Caucus of ACT UP/NY understood the geographic diffusion of HIV as being intimately tied to the island’s colonial status, a position that enabled nonexistent immigration barriers and facilitated unrestricted low-cost air travel. In the summer of 1990, when members of the Latina/o Caucus descended upon San Juan to help organize a local ACT UP chapter, members distributed pamphlets and held teach-ins critical of the island government’s deference to US foreign policy in the region (top image). The caucus was particularly dismayed at the failure of the commonwealth government to secure more Medicaid funding from Congress. Although the vast majority of Puerto Ricans on the island (65 percent) lived at or below the poverty line, making them eligible for Medicaid, the federal government capped Medicaid spending on the island to $79 million a year. That amount compounded with the $300 million allocated by the commonwealth’s government was the financial base for the entire public health system on the island—an arrangement that prevented most Puerto Ricans with AIDS from accessing life-sustaining medications like AZT and Pentamidine. To bring this and other issues to light, the newly established ACT UP/San Juan held a demonstration on August 22, 1990, outside the Hotel Caribe Hilton, which hosted a forum on the “air bridge” linking AIDS on the island to the mainland. About thirty protesters bathed themselves in fake blood, chanting against the commonwealth’s government.[2]

Given that Puerto Ricans, as US citizens, were free to enter and exit the United States, the AIDS epidemic on the island was tethered to that in the US Northeast. That same “air bridge,” however, also allowed the Latina/o Caucus of ACT UP/NY to conceive its efforts transnationally. On the US border with Mexico, matters were quite different. In 1986, the Immigration Reform and Control ACT (IRCA) granted legal status to about three million undocumented immigrants in the United States. But, in doing so, IRCA also fortified the US-Mexico border, rendering it more difficult and violent for Mexicans in the United States to return to Mexico. Thus, unlike Puerto Ricans in New York City who had the protection of US citizenship to rally against the state—albeit as second-class citizens—Chicanas/os and Mexicans in Los Angeles, both immigrant and US-born alike, tended to mobilize against the state’s criminal neglect through cultural production (e.g., art, fashion, performance, and print culture) and service care provision.[3]

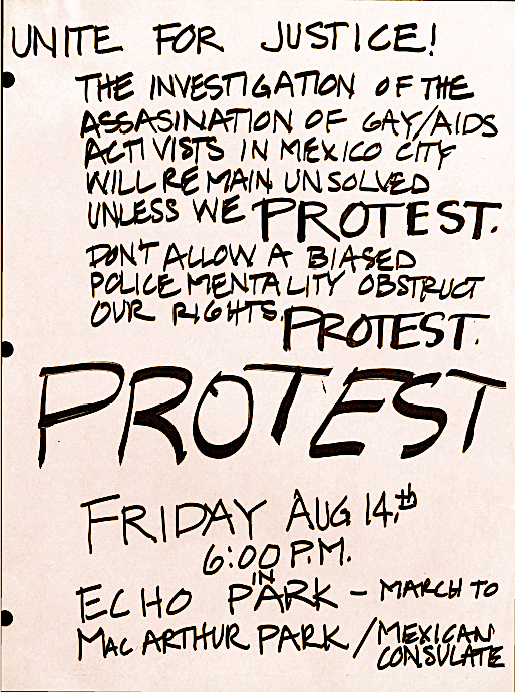

These Latina/o AIDS service care organizations, including Cara-A-Cara and the National Latino/a Lesbian & Gay Organization (LLEGÓ), provided practical support such as meal delivery, assistance with medical paperwork, and legal help against AIDS-related job discrimination.[4] Latina/o AIDS service organizations did participate in public demonstrations including a candlelight vigil hosted by ACT UP/LA in August 1992 in response to the unsolved homicides of seven gay men by “death squads” in Mexico City. In addition to Cara-A-Cara, La Red and Viva co-sponsored the candlelight vigil, which ran from Echo Park to the Mexican Consulate in McArthur Park (Figure 2). Noteworthy here is that the action was a candlelight vigil, a less raucous act of civil disobedience than, say, a die-in.[5]

Another point worth considering when making sense of the differing responses to the AIDS epidemic by Latina/o subgroups is how the lack of citizenship in some mixed-status Chicana/o and Mexican immigrant families compelled queer sons and daughters to take a decidedly less confrontational approach to AIDS activism. They might have done so to safeguard the economic structures and emotional networks orchestrated with family and extended kin for success and survival within the United States. Future scholarship should continue to interrogate how US citizenship, anti-Mexican immigrant policy, and Puerto Rico’s colonial status mediated the particular expressions of AIDS activism by Latina/o subgroups. Such an analysis, in turn, might yield a hybrid model of AIDS activism—both direct-action driven and service care oriented—in the continued pursuit of mitigating the economic and political inequalities that sustain the contemporary racial profile of the AIDS epidemic, both domestically and globally.

Image Credits

Top image: “ACT UP/Puerto Rico.” 1990-1993, Box 16, Folder 3, ACT UP/Los Angeles Records, ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives; “Puerto Rico.” 1986-1997, Box 93, Folder 19, AIDS History Project collection, ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives.

Bottom image: “Action: Mexican Consulate.” August 4, 1992, Box 17, Folder 3, ACT UP/Los Angeles Records, ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives.

Footnotes

[1] “Action: Mexican Consulate.” August 4, 1992, Box 17, Folder 3, ACT UP/Los Angeles Records, ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives.

[2] “ACT UP/Puerto Rico.” 1990-1993, Box 16, Folder 3, ACT UP/Los Angeles Records, ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives; “Puerto Rico.” 1986-1997, Box 93, Folder 19, AIDS History Project collection, ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives.

[3] See, for instance, the recent exhibit, “Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano LA,” mounted by ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives.

[4] “Cara-A-Cara: Latino AIDS Education & Prevention Project.” 1983-1987, Box 55, Folder 28, AIDS History Project collection, ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives; “National Latino/a Lesbian & Gay Organization (LLEGO).” 1983-1997, Box 63, Folder 11, AIDS History Project collection, ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives.

[5] “Action: Mexican Consulate.” August 4, 1992, Box 17, Folder 3, ACT UP/Los Angeles Records, ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives.

René Esparza

2018 LGBTQ Research Fellow, One Institute